These are photos brought in by ex-Twisthands who visited two separate roadshow events in 2019.

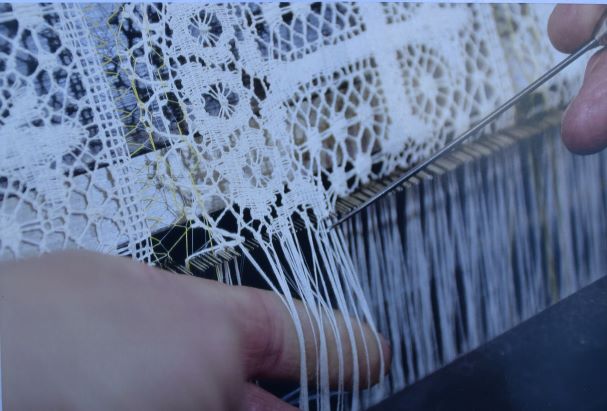

Listening to their recordings gives a real insight into the world of machine-made lace. Taking on the skilled role of ‘Twisthand’ involved a lengthy learning process – both of our interviewees trained at Nottingham Technical College whilst learning on the job, and it was several years before they were allowed to work a full- sized machine on their own in the factory.

Both of them achieved their aspiration to work on the finer gauges of lace (indicated in ‘points’) – ‘you wanted to be a 12 point man’, and Joe’s favourite machine was a 12 point Joseph Cooper machine, which he worked on for 8 years.

Although both worked at different companies before and after, they both spent several years working Leavers lace machines at Guy Birkin and co.

Guy Birkin (incorporating the original Birkin company) was the oldest and largest of Nottingham lace firms. They occupied three sites at Long Eaton, Borrowash and Nottingham, and included their own finishing works. It was later taken over by the Sherwood Group, before finally ceasing to make lace at their newest site in Borrowash, in 2004. Their main clients were large department stores such as Marks and Spencer. As well as the more traditional Leavers lace, they were also known for new types of machine-made lace such as Textronic and Jacquardtronic lace. You can view a 1980’s promotional trade film for the company here (part of the Nottingham City Museums Lace collection): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YWS20_bNkSQ

Lace-making may suggest an image of white, clean and delicate fabric, but the interviews with our Twisthands reveal that making lace on a machine was quite a dirty business…. This was largely due to the black lead/graphite which was used as a lubricant for the machines. They describe how foot boards had to be washed down every week as the black lead made them slippery, and the bucket of cold water kept close by to wash hands when you stayed at your machine to eat your lunch. They also describe the evocative ‘smell of yarn and graphite in the air’. Later, a new lubricating powder was developed and introduced, and one of our Twisthands points out that working with the new white powder meant that you were much cleaner at the end of the day than you were with the graphite. The other, however, wasn’t keen on the new lubricant, having been told to try it on his machine as an experiment. He describes it bringing his machine ‘to a halt’ – ‘it nearly ruined us’. He went back to using black lead after that.

Many of our oral history recordings make reference to the noise in the factories, and lace machines were no exception. One of our Twisthands mentioned that they are ‘quieter now than they were in the 1960s’, but still require ear defenders for workers. It was a feature that inspired him to write the poem entitled ‘Clatter clatter bang bang’ when Guy Birkin staff worked with a writer to create a collection of poems in the 1990s.

The excessive noise in the factories meant that school trips were not allowed to visit, but both our Twisthands remember many other visitors, including dignitaries wanting to see ‘Nottingham Lace’ being made. Joe also recalls a party of ‘women from the Miners Welfare’ being ‘flabbergasted’ at the machines, as they were expecting to see the workers ‘all sat around knitting’!

Guy Birkin and Co were known for their new types of machine-made lace, but like many lace firms, they also experimented with materials. Both our Twisthands recall working with various different yarns such as wool, acetate and silk, describing the beauty of silk on a lace machine catching the sunlight, and the lovely ‘golden lace’ that acetate produced, but the difficulty of working with it when you could not see the semi-invisible threads.

These technical challenges were minor compared to coping with the nationwide labour-relations problems in the 1970s which resulted in the 3-day week. They recall the power cuts, and the site at Long Eaton employing an old fairground generator to try to keep going. This, however, wasn’t powerful enough to run the machines, so they bought their own generator so that they could keep producing orders for Marks and Spencer.

Twisthands could earn ‘good money’, but it seems it wasn’t just the wages that kept them in the role for so long. They remember when the firm would hire a train for staff days out and hold Christmas parties at The Commodore in Nottingham. They both recall the camaraderie at work, and specifically mention having ‘had some good laughs’ and ‘a laugh every day’. Perhaps the experience is best summed up in this quote from one of the recordings: ‘it gave me a life really: family, house, everything’.

Article by Tonya Outtram, Research Fellow, Nottingham Trent University