As we heard in ‘Football, fine lace and supersonic tea bags’, the East Midlands textile industry designed and made a wide range of products. We also heard from our interviewees how the companies often changed their products to accommodate market demands.

Social factors sometimes motivated this change, such as housing improvements (central heating etc) reducing the need for warm underwear. According to our interviewees at the John Smedley’s roadshow event, this was a factor involved in the firm’s move from producing underwear to outerwear. They mentioned the technical differences in their work due to the change, and extra training they were given.

Some changes in product were driven by technological advances, particularly in lace production. Our interviewees from this area often compared the older Leavers lace machines to the newer raschel machines. One of them described raschel lace as ‘not as clean and sharp as Leavers can make’, adding that in his opinion, the Leavers quality came at a price due to the amount of labour required (fewer staff were needed to run the same amount of raschel machines). He explained that it was a ‘different technique altogether, a different world really’.

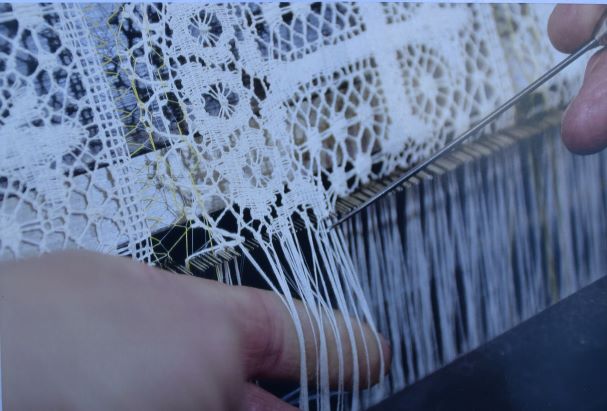

Changes in product often meant different machinery, or new materials, such as new types of yarn. One of our interviewees at our Lakeside event recalled the difficulties of using bri-nylon in the knitting machines ‘because the yarn was very strong it virtually ripped every needle out of the bed if you had a problem with it’. Sometimes, the complexity of the machine itself would present challenges. One of our interviewees who worked at various companies, including A C Gill, recalled training for 3 years to use a smocking machine. She explained that it had 16 needles on it – it would use any number of these, and from 2 to 22 threads. She recalled ’it took a lot of threading up’ as the design could be ruined just by threading one hole wrong, and described it as ‘a very temperamental machine’. Her patience and skill, however, was of great value…She recounted an incident when another local factory had a smocking machine that had been sabotaged (by a disgruntled employee who had been dismissed). They had no-one else who could thread it up, and her expertise was ‘lent out’ to thread it up for them so they could continue to use the machine.

Some of the managers/owners we interviewed from smaller companies told us how they would ‘pitch in’ to help on large orders if required. This lady, recognising her staff’s skills told us ‘I never asked anybody to do anything I couldn’t do myself. I wasn’t as skilled or as fast as them, but I could always fill in’. She went on to explain how the company was able to move into a new specialist area involving complex fabrics, because of the skills already in the factory. ‘Because the girls were so skilled we were able to handle all these fabrics, and not many could’

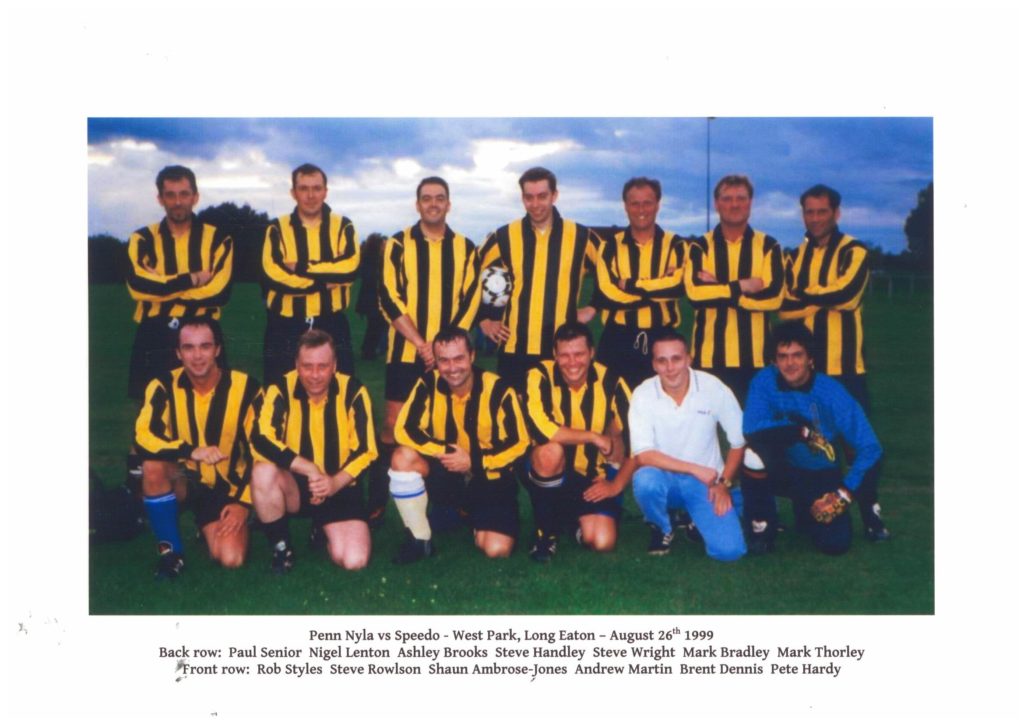

We also heard about the highly skilled area of dyeing and finishing. One interviewee told us about the chemical challenges of dyeing stripes for sportswear (e.g. rugby team shirts) and how it was ‘desperately hard not to get the colours running into each other’. Now retired, he commented on watching the ‘recent rugby world cup’ and some shirts that had not been ‘very well prepared’ – he had spotted ‘colours actually running during the course of the match’!

Our ex-dyer interviewee also claimed that ‘the dyer and finisher is invisible’, explaining that the name of the dyer and finisher is never seen on the label, despite their skill. This could perhaps be said of all the labour involved in creating the many different products of the textile industry…

Penn Nyla football team 1999 (Penn Nyla v Speedo) – no colours running on those stripes! (photo courtesy of Anne Higton)